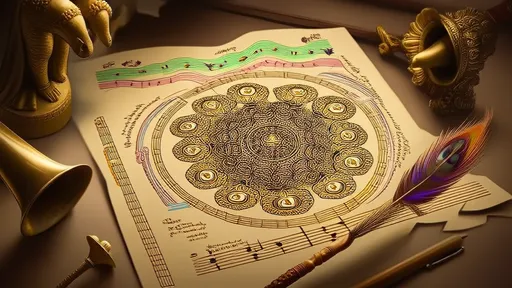

The ancient art of Chinese guqin music has long been revered as a pinnacle of cultural refinement, with its notation system—jianzipu—standing as one of the world's oldest and most enigmatic musical scripts. Unlike Western staff notation, jianzipu employs abbreviated Chinese characters to denote finger techniques, positions, and nuances, leaving rhythm and phrasing to the intuition of the player. In recent years, a quiet revolution has unfolded as scholars and musicians collaborate to reinterpret this cryptic system for contemporary audiences, bridging a millennium-old tradition with modern sensibilities.

At the heart of this movement lies the tension between preservation and innovation. Traditionalists argue that jianzipu’s ambiguity is its strength, allowing each performer to imprint their philosophical and emotional interpretation onto the music. Yet, younger generations of musicians, raised in an era of digital precision, often struggle to decode its subtleties. Projects like the Digital Guqin Initiative have emerged, employing 3D motion capture to analyze the biomechanics of historic performances, translating ancient tablature into dynamic visualizations that reveal previously unnoticed patterns in timing and touch.

One breakthrough came when composer Lin Xia reimagined the 14th-century piece "Flowing Water" using spectral analysis of silk-string harmonics. By cross-referencing jianzipu symbols with acoustic physics, she reconstructed probable rhythmic structures lost to time. Her work sparked debate: purists accused her of imposing artificial constraints, while others hailed it as a Rosetta Stone for guqin’s temporal dimensions. "The notation was never meant to be rigid," Lin counters. "But understanding its boundaries helps us dance more freely within them."

Technology’s role extends beyond analysis. Interactive apps now allow users to toggle between jianzipu and Western notation in real-time, while AI models trained on centuries of oral traditions suggest plausible ornamentations. Notably, the Guqin Cloud Archive crowdsources interpretations from global players, creating a living database of variations on a single phrase—demonstrating how technology can amplify, rather than homogenize, the instrument’s improvisational spirit.

Perhaps the most poignant modern adaptations occur in cross-cultural collaborations. When guqin master Wu Na partnered with a jazz ensemble, she developed a color-coded jianzipu extension to communicate with musicians accustomed to chord charts. The resulting compositions retained the guqin’s meditative essence while absorbing syncopated rhythms—proof that the notation system, much like Chinese culture itself, thrives through adaptive reinvention.

As conservatories worldwide begin incorporating these new methodologies, questions linger about authenticity. Yet the very history of jianzipu suggests fluidity: the Ming dynasty saw major revisions to the system, and regional schools developed distinct annotation styles. Today’s innovations may simply be the next chapter in an unbroken chain of transmission—one where the silent spaces between ancient characters continue to resonate with infinite possibilities.

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025